Morning, recruits! The time is now 0630. I see that you fine men are in your PT gear, sleep-deprived, bleary-eyed, and shivering in the cold. Good! The cold will wake you up – and you better be frosty this morning, ‘cause I got some troofs to lay down to you.

Listen up!

Last time, I covered some things to keep in mind about military service as a whole, and how you should, as much as possible, make it work for you. (Otherwise, the military will gladly make you work for its own purposes.) I also covered the differences between enlisted and officer, and which might be better route for you to take. In short, I recommend that one try to become an officer if you’re doing to be a “lifer,” because life as an officer is relatively easier, is paid better, and garners more respect. However, if you want to do only one tour of duty, then it’s not necessary to become an officer, and it might work against you if you’re looking for some solid job training and experience to set you up in the civilian world once you get out. Officers are trained to be generalists and “leaders,” but also within the parameters of their particular branch. For the short-termers out there, being a “leader” doesn’t amount to much in the civilian world, so don’t get hung up on it.

This time, I’d like to cover the bad of the military. As with anything in life, there’s the upside and the downside. Concerning the military, there’s definitely the bad. But, I must also caution that, to deal with the bad, you must be in the right headspace. As I’ve said before, the draft disappeared in 1973, and the military became an all-volunteer force in the ensuing years. (Though men still had to sign up with the Selective Service, or risk losing some benefits of being an average citizen.)

If you decide to join the military, no one is compelling you to.

You’re free to go to a recruiter, of any service, and discuss options. If the recruiter is indifferent, evasive, blowing smoke up your ass, or is just a plain dick, you can get up and walk out without signing any papers or taking any oaths. You’re free to go to another recruiter, who might be better to deal with, or you can drop the idea of going into the military altogether.

Again, no one is compelling you to do so. That’s your choice, and your choice alone.

But, if you do make the choice, then I strongly recommend you know the good and the bad (and the ugly, which I’ll get to next time). Know enough to make an informed decision. Then, pull the trigger and get things moving.

All right, you maggots. Time to get to the bad . . .

- First off, regardless of what branch you go into (including the Coast Guard), and regardless if you’re enlisted or officer, if this is your first enlistment, you incur a total eight-year commitment in the military. This is also regardless of how long you serve either on active duty, or in the Reserves or National Guard. Keep this in mind to avoid any misunderstanding. If, for example, you take the oath of enlistment on July 1, 2020, you won’t receive your (usually honorable) discharge papers until July 1, 2028. This is if you make it through your first (and maybe second) term of enlistment, and don’t wash out of basic training, maybe are medically discharged, or did something else to get yourself kicked out. If you do just one four-year term, then you will be in the Inactive Ready Reserve for another four years, and are subject to recall.

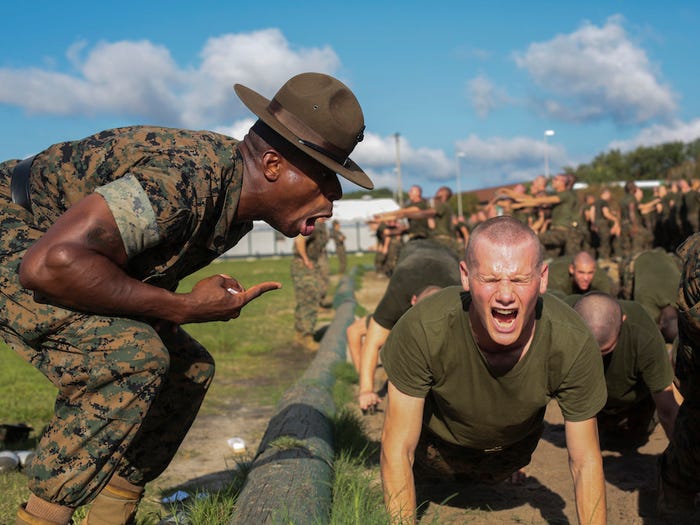

- Your life isn’t entirely your own. (Duh.) You have to do what you’re told, or risk punishment. That punishment could be immediate (“Drop and give me 20!”) or it could be longer term (confined to barracks, extra duty). You could also have non-commissioned officers (NCO) who are intrusive into your personal life (for enlisted), looking over your lifestyle, comings and goings, the people you associate with, your personal property, etc. If you’re not ready to deal with this, then I recommend you rethink going in.

- You could get killed (again, duh) or at least get seriously injured. This is, after all, the military, and you agree to take on this risk when you go in. If you get seriously injured, even while in training, and you get medically discharged with a disability rating, you’ll have to deal with unpleasant things like chronic pain, Veterans Administration (VA) problems, stigma attached to being a disabled vet (often from employers, who don’t want the responsibility of accommodating you), lack of job opportunities, etc. On the bright side, things are nowhere near as bad as they were for Vietnam vets back in the 1970s and 1980s. You’ll garner more respect from John Q. Public, as active duty and a veteran, and won’t be spat upon – in today’s society.

- You might not have a choice with your military occupational specialty (MOS)/job. Though you intended to be a firefighter, for example, you might end up being military police (MP) because that’s where there’s the most need. So, make sure that you go into a branch where there’s a better than average chance to get what you want. Make sure to score as highly as you can on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB). Make sure to get your job assignment in writing. Also, do what you can to increase your chances of getting what you want and have a backup plan: e.g., you accept going into medical instead of engineering as a consolation prize.

- “Doing the 20” (i.e., wearing the uniform until it’s time to retire) isn’t a guarantee. Life happens, and shit happens. You could get so sick of deployments, the people you routinely work with, inane and petty bullshit, etc., to where it’s affecting your physical/mental health and well-being, that you decide to hang up the uniform before the 20 years is up. You could also get injured and be medically discharged, which isn’t in your control and depends on needs of the service branch, how much your command needs you, what some officer says, etc. (Some service branches, because of staffing concerns, are more likely to get rid of “problems” instead of keep them in and do something more constructive with them.) You coud also get married and have kids, and wifey-poo, because she doesn’t like deployments or being stuck home all day with the kids (because she has few job prospects), demands that you get out and become a civilian. The list is endless.

- Some branches are more physically demanding and combat-oriented (the Marines), while others are more like civilians (the Air Force). You might have a rough time finding your comfy little spot, where you can ride things out. You might have expected to have a desk job, only to be out the field for months at a time, doing baby wipe showers (gentle on your ball sac, ineffective for your asshole), eating meals-ready-to-eat (MRE) three times a day, and doing exercises out in the rain and snow. As they say in the military, “Not the one you want.”

- You could miss promotions or have them delayed, regardless of how well you do with your tests, your time in service, time in grade, etc. If there are no open billets, you get no promotion. And, the higher up you go in rank, the less you’re doing your job and the more you become a “manager.”

- Your choice of duty station is often limited, especially during your first term of enlistment, where you’re sent where the greatest need is. And, you could be going straight into a unit that’s getting ready to deploy. Then, you repeat the process when you permanent change of station (PCS) to another unit, never catching a break. Worse, as many Iraq and Afghanistan folks abruptly experienced, you could be stop-lossed, where you’re stuck in your current unit and can’t PCS or ETS.) Lastly, with some branches (e.g., the Air Force), you could get stuck at the same base for years. Sometimes, you could get stuck at a remote base (e.g., Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota or Schofield Barracks in Hawaii) where little is going on or the cost of living is very high where you can’t do much on your piddling monthly pay.

- Even though you have a desk job while in garrison, you still could still be deployed and you could still see combat while deployed. (Again, this is the risk you accept when you go in.) Especially for Army and Marines, remember that, first and foremost, you’re infantry and have been trained to work as such when needed. Your job, no matter what non-combat role it is, comes second. Fortunately, if you have a job that’s mainly support, that will be your job during the deployment.

- Deployments, sadly, are a given in most branches of the military, though there’s a wide spread of different kinds. At bottom, “deployment” means “out of garrison” or “in the field, in a combat zone.” A field exercise near one’s garrison, either in the US or overseas, isn’t necessarily a deployment. Being in a combat zone, is a deployment. Since 2001, deployment has been equated with Iraq and Afghanistan, but soldiers, sailors, airmen, and even some Coasties, have been deployed to places such as Kosovo, Djibouti, Romania, Poland, and Saudi Arabia. Deployments last anywhere from just a few months, up to one year, depending on the service branch.

- Deployments are really where you embrace the suck. Though, I have to say, during my two deployments to Iraq, it wasn’t all bad. If you were on a large military base (e.g., Camp Victory in Iraq or Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan), you could get your own room with a small bed, air conditioning, a decent (but shared) shower, paid wifi, the Base Exchange (BX) and Post Exchange (PX), the DFAC (dining facility) with four meals a day and free-ish (i.e., taxpayer funded) food and drinks. You have morale, welfare, and recreation (MWR) tents where you can take out board games or cards, or watch DVDs. There are also gyms where you can work out 24/7. In short, you’re home away from home, if you modulate your standards accordingly.

- On the other hand, deployment could also mean being at a remote patrol base with no running water, pissing in a tube sticking out of the ground, shitting in a can (where, according to regulations, you have to mix the shit with diesel and then burn it), and coming under mortar attacks and small arms fire every day. Oh, and then there are the convoys racing down the road, trying to avoid IEDs and small arms fire. Fun times.

- Tons of stupid shit, done for no express purpose except that “it’s in the regulations” and because some NCO (especially the sergeant major (SGM) or equivalent), or officer, has nothing better to do and what he (or she) decides to do that moment is the most important thing. One salient example from my days in the Army is how soldiers had to wear berets all the time, unless they were in the field or in the motor pool. This started, according to my understanding, during then Army Chief of Staff Eric Shinseki’s term. The scuttlebutt I heard was that, to push a more “professional” veneer onto the military, all soldiers shifted from wearing patrol caps, which had been part of the uniform for many years, while in garrison to wearing berets. (Also part of the scuttlebutt was that Shinseki had financial interests with the company that manufactured the berets.) All during my time, I had to wear the beret except in the motor pool, and so had to carry around two hats with me all the time, switching the one for the other constantly.

- There’s lots of shitwork for enlisted to do. There will be many times when, both in garrison and while deployed, there’s, quite frankly, “nothing to do.” You’ve finished with your tasks and now you have some “free time.” Oh . . . oh . . . silly boy. No such thing, really. As lower enlisted, you’re “free labor” to dig ditches, clean out storage closets, be chauffeur to other personnel, drive Humvees and 5-ton trucks around, and be the pack animal. There’s always plenty to do in this department. It’s times like these when you wish that you were an officer, because they push paper and sit in meetings while in garrison. Other times, they walk the general’s dog.

- Very few jobs out there in the civilian world for military, unless you choose to be a war-zone contractor, work for the Federal or state or local government, the police, or manage to get an in-demand skill that has open positions. This is regardless of how bad-ass you were while on active duty. If you don’t have the skills and the experience, then you don’t get to pay the bills, and might have to reenlist to eat and stay off the street. So, think carefully about your job and choose wisely.

Finally, though one obvious benefit you have is that you can form close bonds with other guys in your unit, there are some prominent caveats here. For one thing, everyone is an individual and acts as such. You and the other guys, and gals, were certain people at the time you enlisted, went through basic training, and when you arrived at your first unit. Basic training made you a soldier, sailor, airman, Marine, or Coastie. But, you did not magically erase any things happening under the surface, which surely is going to affect how well you perform while on active duty and how well you relate to others.

For example:

Were you a mama’s boy? Were you daddy’s little princess? Were you a sheltered kid?

Did you come from a single-mother household, and was your father maybe in jail?

Did you grow up in poverty? Did you live in a trailer park? Were you ever homeless?

Were you physically, mentally, or sexually abused? Have you ever acted out because of this trauma – most likely undiagnosed and unprocessed?

Do you have problems with substance abuse? How many times a month do you get black-out drunk?

Do you have a college degree and think you’re smarter than everyone else?

Do you have a severe inferiority complex and feel the need to play hero?

Do you come from a military family and are you under pressure to “carry the torch”?

Do you have a problem keeping your dick in your pants or your legs crossed?

I could go on, but I think you get the picture. As one guy from my first unit said, “You were a certain kind of person before you came into the military.” You’ll very likely remain that person, unless you display some self-awareness and work to get rid of, or at least minimize, the uglier parts of yourself.

Secondly, small groups and cliques will unavoidably form, even though everyone is in the same unit and wearing the same uniform. (This starts with rank.) Those that are married and have families, or who are permitted to live off post because of their rank, won’t hang around with the singles in the barracks. You’re not likely to always have cohesion with your team members, or the people who work in your shop. At my first unit, my NCO and I didn’t get along, and he caused a lot of tension in the commo shop. Once he left the unit to go elsewhere, things calmed down significantly. At my second unit, I pal-ed around with a few “misfits” from the other shops, because they had their own friction with the guys in those shops. You form alliances against the shitbags and fucktards a good deal of the time. Us vs. them. I know, this flies in the face of “one team, one fight,” but I’m laying down unpleasant truths here.

Lastly, once the people you’ve worked with PCS and go to another unit, or are getting out of the military altogether, unless either of you keep up the relationship, it will wither and die. The lack of upkeep could come from either end. In my case, there were certain people with whom I had a good working relationship while in the same unit with them, but I didn’t hesitate to leave them behind once that working relationship was done and I never had to deal with them ever again. Ditto for them once they became civilians, and this is despite them being just a few hours’ drive from me. On the flip side, those guys that I was interested in keeping in touch with, didn’t hesitate to tell me to fuck off on their last day in the unit. Basically, people, on their last day, will simply finish their affairs, say nothing to anyone or might say goodbyes to just a small handful, and drive off in their car. Or, they might have a big going-away party. Or, they take pains to tear some of their fellows a new asshole, releasing the pent-up frustration and hostility toward that person they’ve had for a year or two. Lastly, I saw this only with enlisted; I didn’t see anything with officers so I can’t comment.

All right, troops, I’ve said enough this time. If I’ve brought you down, get over it. Better that you hear this from me instead of a recruiter, or some former military dude who only wants to talk about the “glory days.” It gets worse, trust me, but that’s for next time.

Dismissed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.